-

Death Wells Remains of Assad's Victims Contaminate the Crops of the returnees

Musab Al-Yassin - Farid Mahlool

Faisal al-Buasi stands on the edge of a well in the middle of his land, planted with olive trees for decades. The thirst is threatening to destroy them, and he is confused and hesitant in his decision between watering the trees with water polluted by human remains, or waiting for the rain—a gamble with an unknown outcome.

Faisal said:

For 14 years I have been away from my land, my only source of livelihood. Today I returned from a long displacement to find some of my olive trees cut down, and others withered from thirst. To make matters worse, I have a well full of water in the middle of my land; however, I am very worried and fearful for the future of my thirsty olive trees, because they are being irrigated with water contaminated with human remains. The regime forces turned the well into a mass grave, throwing in the bodies of more than 30 people after killing them in several locations in the eastern Hama countryside." In five underground and surface wells scattered across the Hama and Idlib countryside, residents and civil defense teams discovered human remains, including those of women and children, who had been killed by regime forces and their allied militias. The discovery of remains in water wells has become a widespread phenomenon in several Syrian governorates formerly controlled by the regime.

Map

https://www.datawrapper.de/_/2D070/

This investigation documents crimes with a consistent pattern: extrajudicial killings and the concealment of victims in wells in Idlib and Hama governorates. Relying on open-source information, eyewitness testimonies, data analysis, and official government and humanitarian reports, we reveal the Assad regime's responsibility for these systematic killings and the crimes of concealing victims' bodies.

The investigation team worked in the towns of at-Tlisiya, Maan, Kafr Nabudah, and al-Bani in Hama countryside, and Hazarin and Maarat al-Numan in Idlib countryside, where human remains were found in underground and surface wells.

At-Tlisiya Well

Jawdat Ali al-Muhammad, from Maan village in eastern Hama countryside, never imagined he would one day retrieve the remains of his three brothers with his own hands, searching for identifying marks on their clothing among piles of human remains to confirm they were indeed his brothers, whom he had lost in the summer of 2012.

According to Jawdat, a group of pro-regime militiamen from at-Tlisiya village, east of Hama, arrested his brothers, Khalid, Farhan, and Mithqal, from their family home in July 2012 and took them to at-Tlisiya. They disappeared until the summer of 2015, when Jawdat found their remains in an artesian well along with the remains of 29 other people. Some of the remains were identified by their families, while others remain unidentified at the time of this report.

In June 2012, residents of the villages of Karah, Maan, and Ras al-Ain discovered the remains of 32 people—including women and children—in a well on farmland in at-Tlisiya, east of Hama. The well's owner was irrigating his land when he was shocked to find human remains floating on the surface of the water, according to Anwar Muhammad al-Assi, from Karah village in eastern Hama Governorate.

Al-Assi said that his brother's body had been in the well since 2012, and he was aware of it, but he couldn't locate the well or search for it due to the presence of regime forces in the area.

One evening in June 2015, al-Assi went to the well near the village of at-Tlisiya, where he and his relatives worked to retrieve the remains. There, he identified his brother's body by his clothing and the bullet wound in his head, which had killed him and two of his cousins.

According to a video saved on a memory card by a member of the regime's militias, that member and a group of others killed three people in a pickup truck in 2012. Among the victims were Anwar's brother, Muhammad al-Assi, Fadi al-Assi, and his cousins.

Video

Anwar Fawaz al-Ramadan, from Ras al-Ain village in eastern Hama Governorate, identified the bodies of his brother, Yasser Fawaz al-Ramadan, and his cousin, Ahmed Badr al-Mutair, by their clothes and shoes, some of which were still intact, at the bottom of a well in at-Tlisiya.

Anwar said:

In 2012, my brother Fawaz and my cousin Ahmed were heading to Hama city when, at the Tal Bazam checkpoint, a group of regime thugs from the village of al-Talisiya stopped them and killed them on sight, according to an eyewitness.

Before the Red Crescent and Civil Defense teams arrived at the Talisiya well, a number of young men descended to the bottom of the well and discovered a large number of bodies buried under large stones, in addition to hand grenades found at the site. According to Mahmoud Ali al-Assi, the young men worked for hours to retrieve the bodies. He noted that the well had not been completely cleaned, as another pit connected to the well's bottom still contained human remains.

Upon arriving at at-Tlisiya well, the investigation team met Ahmad al-Khalaf from al-Qahira village, south of Idlib, about two kilometers from at-Tlisiya. Ahmad said that in 2012, he witnessed militiamen from at-Tlisiya kill three young men traveling in a pickup truck. The militiamen stopped the vehicle, forced the young men out, and opened fire on them. He confirmed that the victims were Fadi al-Assi and his cousins.

Military Divisions

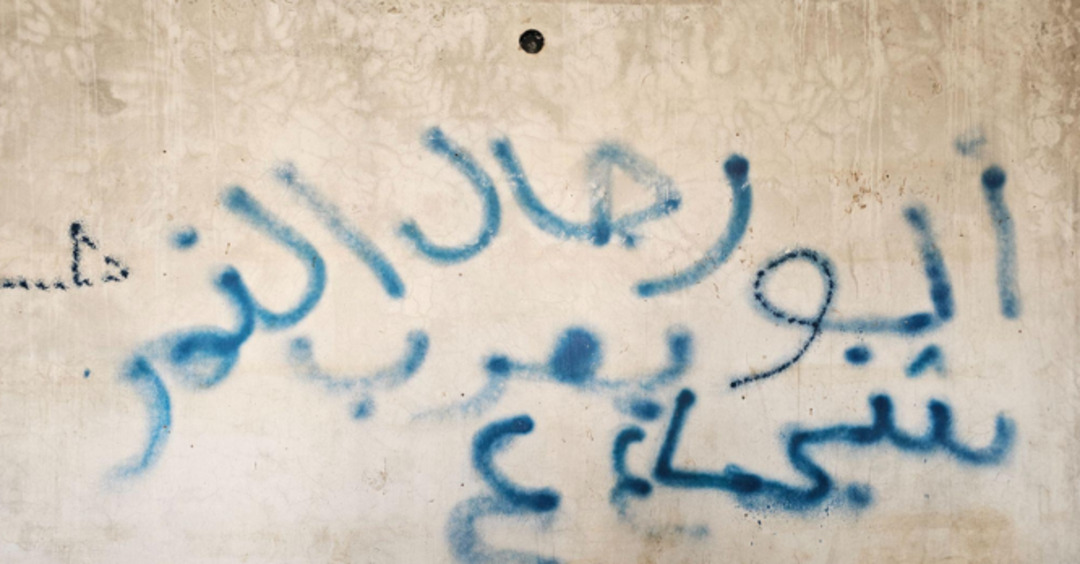

Photos taken by the investigation team in their tour of at-Tlisiya and its surroundings document graffiti on the walls of remaining houses and shops. This graffiti refers to the 25th Division of the former regime forces, with some mentioning the name of Suheil al-Hassan, the division's commander, known as "The Tiger."

The 25th Division is located about three kilometers from at-Tlisiya village. Its military checkpoints were scattered throughout the area from which the villages of Karah, Ras al-Ain, and Khafsin had been forcibly displaced. Meanwhile, the residents of at-Tlisiya, Maan, and Zaghba remained in the area for approximately thirteen years. When the residents of Karah, Khafsin, and Ras al-Ain returned, they found their homes completely razed to the ground.

Graphic writing on a house wall in the village of Karah, east of Hama

Unidentified individuals

With the return of the forcibly displaced to al-Bani village, near the Kafr Nabudah city in the western Hama countryside, after a five-year displacement, one of the residents began cleaning his house, including his artesian well, of the remnants of war and shelling. Needing water, he attempted to draw water from the well using a rope and bucket, but the bucket was filled with human remains when he pulled it out.

According to the Syrian Civil Defense, its members recovered seven sets of remains from inside the well. Initial assessments indicate the remains belong to six men and one woman. A local resident identified one of the remains as belonging to a member of his family. According to testimonies from villagers, the identified remains belong to a civilian who was killed by the Assad regime in 2013 and whose body was thrown into the well.

Journalist Mohammed Amin said that regime forces killed his mother and sister in the family home near the village of Al-Bani, then disposed of their bodies in a well during the winter of 2013.

Interview

Mohammed Amin based his information on a call he received in 2016 from a former regime soldier who told him that his mother and sister were shot dead in the family home.

According to photos obtained by the investigation team from the family home after the fall of the Assad regime, bullet holes are still visible in the living room. Military expert Majed Al-Mahmoud says these holes indicate that the shots were fired in bursts from Kalashnikov rifles, the type of rifles used by the former regime forces. In 2013, the Fourth Division, Regiment 555, Battalion 584, led by Colonel Samer Muhammad from the village of Jabal Ain Sharqiyah, was stationed in and around the village of Al-Bani, while the sector commander was Colonel Muhammad Saqr from the village of Ain Al-Krum, in addition to the Eighth Division, Brigade 33, according to military observer Aknaf Al-Ali.

Not far from Al-Bani village, specifically in Kafr Nabudah city, the Civil Defense announced that it had received a report of human remains found in a collection well in ar-Rabiya neighborhood, north of the city. According to residents, the remains may belong to three young men of similar ages who went missing in 2019 on the outskirts of the city during the regime forces' advance. Residents noted a match in clothing between the missing men and the remains found, and the initial assessment indicated that the remains belonged to three individuals of similar ages.

A Grave Within a Grave

In a tour of the eastern Hama countryside in June 2025, the investigation team encountered a man standing near a cemetery in Maan village on a hot afternoon. The team stopped to inquire about his presence and discovered that the man came to the site daily, attempting to dig up a well dug within the cemetery, claiming that his relatives had been killed and their bodies thrown into it.

The Hama Governorate announced on its Facebook page that residents of Maan, a town in the northern Hama countryside, found approximately 15 bodies inside a well. These bodies belonged to civilians killed in 2012 by groups loyal to the Assad regime. This is the same mass grave documented by the investigation team.

A relative of the victims, Abu Khalil, stated that his aunt, two brothers, cousins, and women from his family were killed by local militias, numbering around 30 people, and their bodies were thrown into the well. Nut shells and stones were piled on top of the bodies.

The situation is similar in Idlib, where forces of the former regime, supported by local and foreign militias and the Russian air force, have seized control of the southern Idlib countryside. This included areas such as Khan Sheikhoun, Maaret an-Numan, and Kafranbel, extending to Saraqeb and dozens of surrounding villages and farms during the winter of 2020.

According to military documents obtained by the investigation team, the Fifth Assault Corps (the regime's Third Brigade) was stationed in Maaret an-Numan area and the surrounding villages and towns.

On April 10, 2025, the Syrian Civil Defense (White Helmets) announced that they had recovered human remains from a sewage drain in Hazarin village in southern Idlib countryside. This village was forcibly depopulated and captured by the Assad regime between 2019 and 2024. The investigation team explained that the initial assessment showed signs of gunshot wounds on the bones.

Justice for the Victims

Collecting the victims' bodies and throwing them into wells has two aspects: the first is concealing the crime by moving the victims' remains from the places where they were killed, thus rendering them legally missing, according to lawyer Abdul Nasser Houshan. Another aspect relates to the fact that throwing bodies into wells saves the time and effort of digging mass graves.

Concealing a body is a crime separate from murder, punishable by imprisonment for a period ranging from two months to two years, if the intent was to conceal the death, according to Article 468 of the Syrian Penal Code.

It is also considered a form of criminal complicity in murder if the perpetrator knew the perpetrators' intent and helped them conceal the crime—hiding the body and evidence—according to Paragraph (e) of Article 318 of the General Penal Code.

Abdul Nasser said that justice for these victims will be achieved by identifying them, then investigating the circumstances of their disappearance and murder, and prosecuting the accused.

The head of the National Commission for Missing Persons, Muhammad Reda Jalakhi, explained in statements to SANA news agency that the commission has developed a six-stage field action plan. The period ranges from three to six months, and the organization has a map containing more than 63 documented mass graves in Syria, with estimates indicating that between 120,000 and 300,000 people are missing, and perhaps more due to the difficulty of accurately counting them.

According to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court of 1998, enforced disappearance is classified as a war crime and a crime against humanity. The killing of civilians is also considered a crime against humanity, under Article 7 of the Statute.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) defines missing persons as individuals whose fate or whereabouts are unknown to their families, or who have been declared missing based on credible information, in the context of an international or non-international armed conflict, as a result of acts of violence or internal disturbances, or in any other circumstance requiring the intervention of a neutral and independent mediator.

The term "missing" refers to people who may be alive or dead, and this uncertainty itself constitutes a source of extreme vulnerability and danger. If they are alive, they may be secretly detained or separated from their families due to sudden displacement, a disaster, or an accident. In both cases, they must enjoy the protection afforded by international humanitarian law to the category to which they belong; whether they are civilians, displaced persons, detainees, prisoners of war, wounded, sick, dead, or other categories.

The Geneva Conventions also stipulate several obligations that parties to international armed conflicts must fulfill, including taking all possible measures to clarify the fate of missing persons, searching for persons declared missing by the opposing party, and recording information about these persons.

How do human remains contaminate water?

According to a joint press release from the Red Cross and the World Health Organization, the presence of bodies near or within water supply facilities can cause health problems. Bodies may release feces and contaminate water sources, leading to the risk of diarrhea or other diseases. Bodies should not be left in contact with drinking water sources.

Kafaa Al-Deebo, Nutrition Coordinator at the Qatar Red Crescent Society, says that, according to scientific and health standards, the mixing of human remains with drinking water sources leads to microbial and chemical contamination. The decomposition of bodies releases viruses, bacteria, and parasites that cause a range of serious diseases, such as cholera, typhoid, and hepatitis. In addition, the decomposition of these bodies releases metallic compounds. For example, ammonia, phosphates, and heavy metals can remain in the water for extended periods, causing chronic illnesses in the long term.

Despite the fact that the remains have been in the well for over 13 years, the danger persists. The decomposing minerals from the bodies constitute a source of pollution for many years, especially in shallow wells.

The effects of this pollution extend to all age groups, but children are more vulnerable due to their weaker immune systems and the rapid accumulation of toxins in their bodies. This can lead to severe diarrhea, cellular problems, and neurological and cognitive developmental issues. Adults, on the other hand, may suffer from hepatitis and nervous system disorders. Therefore, before using the water from these wells, it must be analyzed, and the wells must be disinfected and treated.

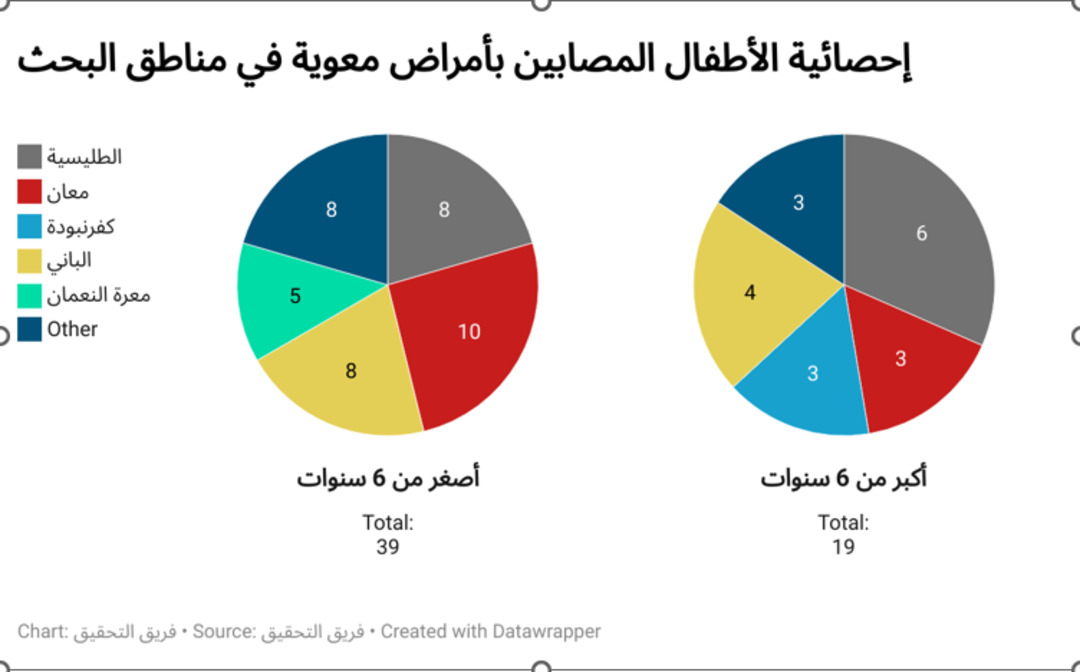

A local survey conducted by the investigation team in areas with wells suspected of containing human remains revealed that 58 heads of households reported their children under the age of 11 suffering from abdominal pain caused by intestinal infections. This resulted from consuming contaminated water or food after returning to their towns from displacement during the first half of 2025, according to information provided by doctors and pharmacists in the area.

https://www.datawrapper.de/_/dLYSi/

ترجمة الشكل:

Statistics of Children Infected with Intestinal Diseases in Research Areas

Younger than 6 Years

Total 39

Older than 6 years

Total 19

At-Tlisiya

Maan

Kafr Nabudah

Al-Bani

Maaret an-Numan

Other

The investigation team contacted the Hama Governorate Water Resources Directorate to inquire about the measures taken by the directorate regarding the contamination of wells with human remains, and whether it had disinfected those wells. However, the team had not received any response from the directorate by the time of publication of this report.

This investigative report was prepared by the journalist as part of a project implemented by the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression, with the support of NED and under the supervision of Mr. Ahmad Ashour. It reflects the views of the author only

You May Also Like

Popular Posts

Caricature

opinion

Report

ads

Newsletter

Subscribe to our mailing list to get the new updates!